Shortest Stories

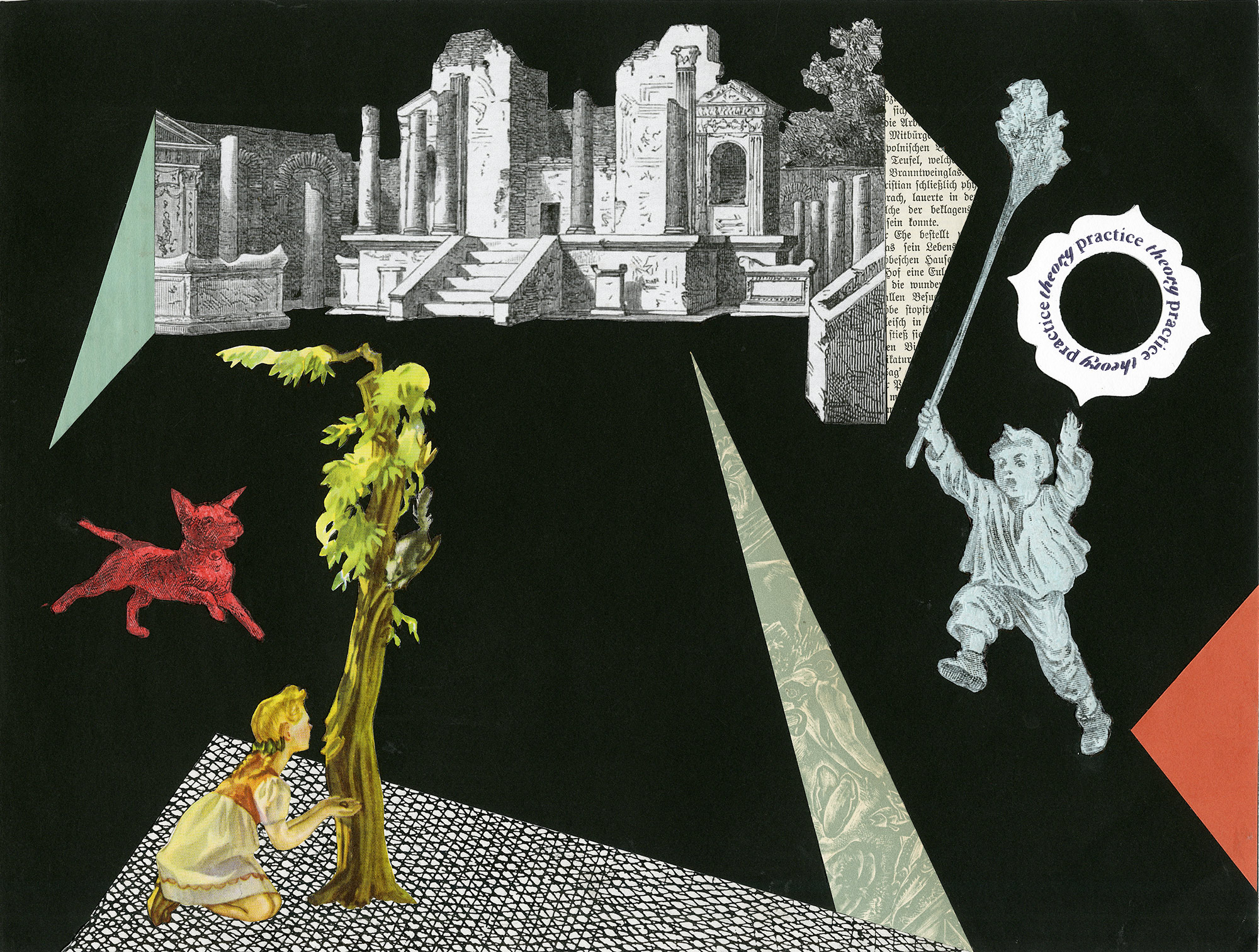

A complicated, lifelong relationship with the printed word lies behind my exploration of books as both physical material and subject matter. A current primary source—both for sculpture and for collages-- is the library left behind by my grandmother Mary Löw, a citizen of the late Austro-Hungarian Empire who avidly read many English classics translated indifferently into German. These unwanted volumes (printed in a Gothic script now legible to few) are destined for landfill, so their new life as art: whether used as books or as fragments of illustration and text, functions as reclamation of their value and, at the same time, serves as an uncomfortable recognition of the decreasing role of books in a digital media world.

Each collage in the Shortest Stories series, containing a mixture of Old World images and text and figures from 60’s readers, bits of sheet music and other random ephemera, is titled with the entirety of an abbreviated fiction. Selected from 100 Shortest Stories, each of these pieces of writing represents a mixture of memoir and fantasy, evoking styles ranging from detective novels to fairy tales to pulpy romance bodice-rippers. The aggregation of images in each work on paper is intended to represent a complementary reading, rather than serve as a literal illustration.

14

Over and over, she read the last few lines on the page. They could mean the end, or a new beginning. But was it new? No start can be really fresh, anymore. They’ve all been used. A hundred times. The best she could do, she surmised, was to settle for in medias res: to start in the middle. Methodically, she ripped the manuscript pages to that halfway mark, one by one. Settling again on her small, hard chair, she began to read the last lines on the page. They could mean the end, or a new beginning.

20

Bitter, salty fluid stings her nose and eyes, as she feels herself sink to the bottom of the bay. Tossed there by a monster, she fears returning to the churning surface, but-- lacking the equipment to breathe in the sea-- she claws her way up towards the paler green. As her head breaks through the small, scummy waves, she can hear the beast roaring. “Hey Lindy!” he shouts, a smile as ugly as a flesh wound splitting his big red face. “How’s the water?” Closing her eyes, she sinks again. He will figure it out sooner or later: this is no way to teach someone how to swim.

85

There were piles of salt in the corners of every room in the house. She was trying to get rid of the odd, cold sounds that seemed to seep out of closets and floors-- the memories, she thought, of someone who had lived there because there was nowhere else to go. Not a prisoner, exactly, but close enough. Was it something about not being able to love? Or, maybe, live? It wasn’t clear. Finally, she learned that a son of the woman who had sold her the place, a boy deaf from birth, had never been allowed to go to school and learn how to sign. When the others left he had stayed behind, his mother’s companion as she slowly went blind.

24

You didn’t believe it when it happened. I know that. But no one could have possibly imagined that she’d go that way. All I can tell you is, the day was beautiful—warm for January, some 40 degrees, and we went outside the back door just to listen to the birds. They were going nuts, yelling at each other and jumping around, so Juney waved her arms and started to sing right back, in that screechy voice of hers, and I guess the vibrations just knocked it down. The icicle hanging overhead, I mean. Heck, James—she was ninety-nine, and couldn’t remember a blessed thing beyond her dead twin sister’s name: Willa, lost to influenza before they turned sixteen. Now they’re together, after eighty-some years. Wonder if they’ll even recognize each other-- one so old, the other so young. Or maybe, they will look just the same, in that other place.

88

Night after night, she would tell them a story, their Scheherazade: a story about them, their pets and possessions, the big stone house where they lived with a dragon, the benevolent wizard whose lessons were disguised as adventures and games. They had a circus with animal acrobats; they journeyed through a forest with talking trees; became fairies, went to dances, and flew through the air, over and over. When she started each evening she knew nothing about where events would lead—except, that magic would surely be involved. That, and all she believed and loved.

89

Starting very early while the shadows were still long, we walked from yard to yard, picking up the bodies that had fallen from the trees, during the night. The day before, men on trucks had passed through in a futile attempt to stop the blight that eventually killed all the graceful elms. But the spraying had—unforeseen consequences. In a shoebox marked “Eleven Dead Birds” with colored pens, we buried them together, in Scott’s backyard. His mom got really mad when she found them, months later, while planting out her bulbs, but it didn’t seem right to just throw them out.

68

It’s winter, raining hard. We are trying to snooze, sweaty mammals huddled close, but a gutter has ruptured on the house next door, releasing a stream straight down thirty feet to a fan of cement five yards from our bed. Stop twisting the covers into knots, he says. Just pretend it’s the freeway at rush hour, you’ll sleep. Somewhat soothed, I close my eyes to an imagined gridlock of fish and naked divers, accompanied by the tinny sound of mandolins, being swept out to sea.

86

If there were a place to go, we would have gone there. Nothing remained except pieces of half-remembered landscape, corners in cities we had lived in and left. One day I came home, and he had taken his collection of 50’s radios and packed them into boxes stacked by the door. After a few days, I understood. Leaving the key tucked under the mat, I called you and asked you to come and get me, before I disappeared.

80

"I make my living," he said with a shrug, "by fixing the things other people break—whether through stupidity or accident, it hardly matters. The outcome is the same. Shards or shreds come back together until the place where they were once apart is invisible, stronger than it was before." His eyes narrowed as he faced the door. "If only the mistakes were not repeated. The cruelty resumed. The criticism voiced for a thousandth time... If only, in other words, your dearest mother was more like a vase."

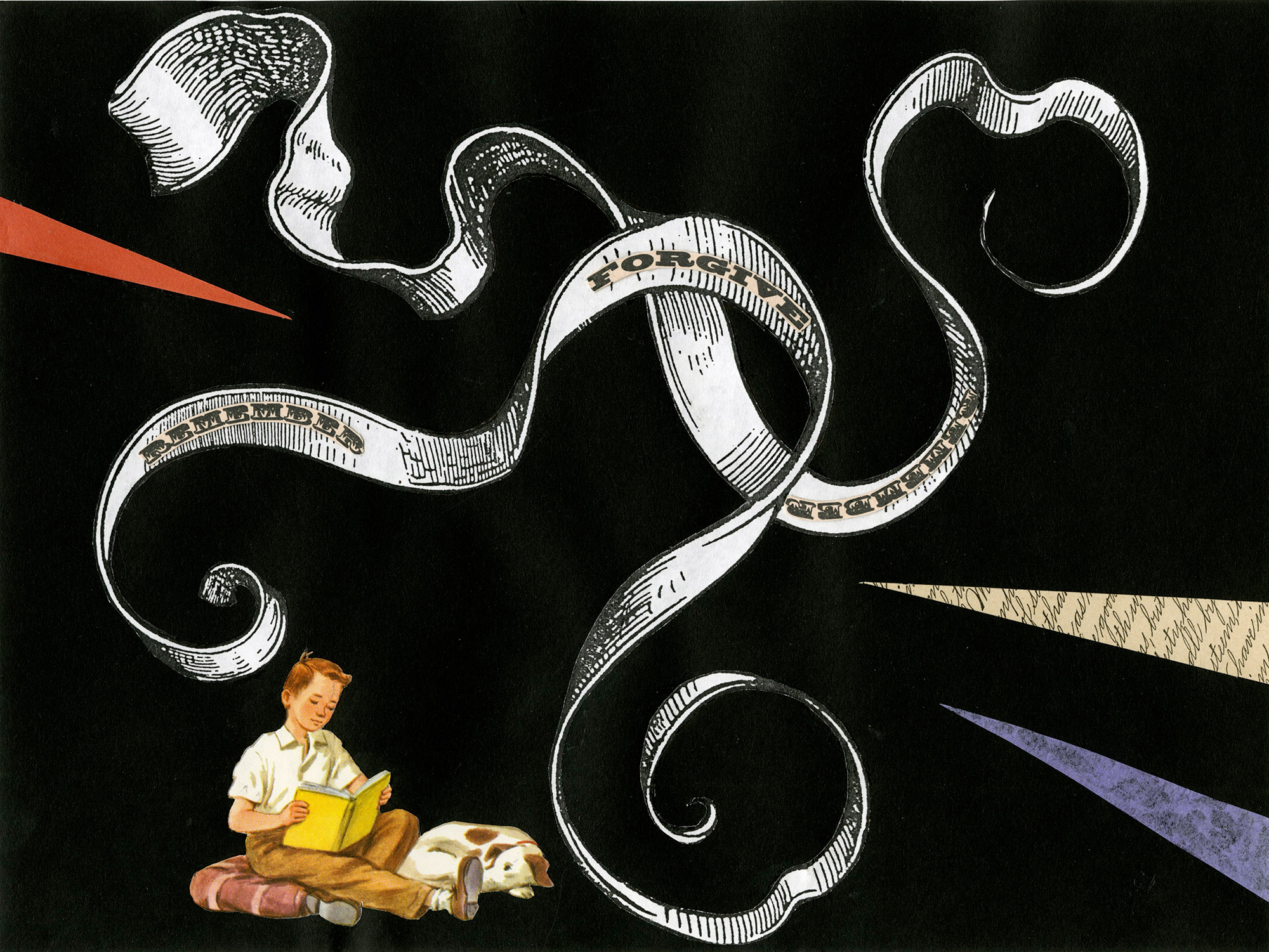

5

Forgive and forget. How could anyone follow this rule? We try, because letting go is the only way to drop the burden of anger or grief. Yet remembering could mean that the source of the pain won’t be repeated—at least, not as easily as before. Forgive, and remember. Get on the train, even when you know what lies ahead, at the end of the line. There may be an unexpected chance to change tracks and arrive at another destination, if you pay more attention to the trip itself.

47

The problem with language is that it is made out of words. I can tell you about a person, a place; a smell, a sound, or a quality of light, but my description is just an abstraction of the things I am talking about. Although a word can evoke a feeling (and often does), there is no guarantee that the contents of a powerful phrase: the associations that lie beneath its skin, will be the same for you that they are for me. Unable to enter each other’s minds, we can never be sure that our experience of things truly coincides—that the color of the sky or the taste of rice is the same for us both. All we really know (or think we know) is that what we call rice isn’t what we call blue.

7

I closed my eyes, suddenly remembering the game we used to play on the continuous slope of lawn that extended from house to street, an expanse of green interrupted only by the concrete lines of sidewalks leading to every house. Mother, may I, we would ask, before hopping, creeping, whatever was commanded, towards the Mother of the game. If you forgot to ask for permission you had to go all the way back to where you started. Usually, that meant you would lose, but it was possible that everyone else, just as eager to advance, would also forget. It could happen. In fact, with a rare, poetic justice, it just had.

91

In the village, we all knew what the red line meant, painted on the side of the old man’s shed like a careless crayon mark in a little child’s book, dashed across a picture in a moment of pique. It was the line beyond which no one ever was to go: where you left his mail or milk, or anything else. For years, I believed he had painted it himself, setting out a distance inside of which he lived, outside of which we stayed. It wasn’t until I was nearly seventeen that I realized his limits were set by someone else, the day the sheriff came and scraped the red paint away.

10

All I remember is turning around. Seeing grass and a bed of flowers, my nose and mouth filled with a really bad smell. Nothing that has happened before that moment—no person, place or thing—remains on the screen inside my mind. I don’t know my name, my age, my address; wearing clothes that are odd but mended and clean, I speak English with no discernible accent. No one claims me and that is that. For two decades, that moment in the park is my birth, at the age of around sixteen, until the day the building explodes around me, and the past comes back. In the hours I wait for someone to find me, I review my childhood with amused disbelief. As it turns out, I was raised by wolves.

63

How can we measure memory? From moment to moment, different events rise to the surface, demanding retrieval from the river of time. Even when we linger in the same damp spot to savor a second of shared spectacle, the images lodged in our separate brains are never the same, colored as they are by our different pasts. It’s like shadows of a hand on a parlor wall: where one sees a wolf, another sees a dog.

54

It seemed right that they were together back then. They were both connoisseurs of sensory experience; unlike the rest of us, who went at acquisition in the usual ways (drugs, sex, foreign travel), they had carefully put their impressions together as exactingly as stamps or guns or wine. Once, I accompanied her to a place where the scent of a rare night-blooming vine made an island of strange but pleasant perfume. We stood in the dark without talking or moving for quite a long time. Soon afterwards, though, she left on an expedition from which she never returned. Maybe they had argued. Maybe she knew that he was losing his sight. I think sometimes of that evening I spent with her as a part of a collection of which only cryptic fragments--like this story-- remain.

28

My sister could read anywhere, even in the car. By opening a book, she removed herself from the picture so thoroughly that she might as well have been erased. You would call her name several times, and when she finally looked up, her eyes blank and black, you felt like you had done something really wrong by pulling her back. I didn’t find my own secret passageway out for another ten years. Not surprisingly, it led to a different kind of place.

65

Weigh, measure, balance. Finger and thumb approach each other in a gesture of assessment, questioning the size of something hidden outside of the picture. Animal, vegetable, or mineral? Soft, or hard? Feeling or fact? In a cryptic language of signs known only to those who have experienced faith, a reply comes back, as if from a distance: approach with—passion? Caution? Kid gloves? As you squint to interpret the waving hand’s final blurry mudra, it melts away in the static-charged air.

38

The same six shapes, crowded together, still line the side of the peeling corner house: a cube, two spheres, and strange, irregular polygons, made up of carefully barbered twigs and leaves. Walking the blocks at night, I count the yards where this kind of topiary grows. Fewer every year, as the houses turn over; couples with babies rip out their lawns, letting shrubs return to their natural state-- whatever that means, in a place where almost everything that grows in the ground came from somewhere else.

6

Why are we like our parents? I looked at the words on the page, incredulous that anyone would have to ask. Even without the tiny map embedded in every single cell, we would have no choice but to follow, mimicking each pigeon-toed footstep, moment of compassion, angry thought or misguided dream. Briefly, it crossed my mind that it must be hard for orphans—never knowing why you feel an impulse or can do certain things without learning how. I closed the book and made another mark with a sharpened stick on the calendar I had drawn on my cell’s peeling wall.

53

None of them knows how to stand or sit in a way that seems natural, and they argue with their arms, never having learned how to use their hands. Coming in, I see them, lying dazed on the furniture or shifting anxiously from foot to foot. No one hears me as they shout at each other, repeat the same questions over and over, ignoring the same answers. Late into the night, they continue to debate while, out on the lawn, I see myself as a child of five, crouched by the glowing squares that fall from the windows above. She is looking under the light, searching for some kind of opening or door. What isn’t clear is whether she is trying to find her way back in, or get out.

22

Brett thinks that broken glass looks like ice, sparkling in the dull grey midden of knee-deep trash and smelly dirt that surrounds the house. The pointed shards are so pretty and bright in the morning sun. There is one clean spot on the grimy window, and he likes to sit on the floor and put his eye to that little hole of light. It could be a peephole in a fence around a field of diamonds. A telescope, revealing distant stars; a wormhole into suspended time-- since no ice would last but a moment, in the sweaty, wet-blanket heat of summer in this place. But he knows nothing of these things, having only rarely set foot outside these walls, where three kids live alone without help or harm.

9

Open up, I willed the metal box. A smooth, six-sided object, it had no visible means of entry, but I was dead sure that there was a trick. Some subtle pressure, or a series of taps; maybe, if I sang it a special song, or shone a colored light on its silvery planes. But there was no time left for solving this kind of smarty-pants puzzle. Picking it up, I staggered to the window and started to swing its considerable weight towards the glass, hoping that a forty-story fall would do the trick. When I felt a panel slide beneath my left hand, it was almost too late.

35

Her hair is curliest deep below the surface, at the nape of her neck, where only my hands ever manage to touch. I remember reading once that there are places in the

South where this spot is called, with affection, the kitchen. Twisting the blondest curls into a braid, I reach deep down for the tighter spirals, darker than the rest, and pull them in, smoothing them out. Who will tend her hair when she finally leaves? She is much too old to be coming to me every morning, complaining of her tangles and knots. I stroke them gently into some kind of order, from the kitchen on out, and send her on her way.

39

In the middle of the night, ideas like to present themselves, so clearly worth remembering she always tries to force herself to hold them in her mind. She repeats them to herself, over and over, thinking that she really should turn on the light and write them down. But she never does; it would wake him up, or she would never sleep again. In the morning, nothing but the memory of the vision’s luster remains. She finds single words in the notepad function of her phone, one after another: Tears, stare, steer, trees, tease, seats. Still half asleep, she taps in four more: from, form. Text. Exit.

40

All the stories they told each other were about some harsh dystopic future world, where everything had run out or died: tales of privation, oppression and loss. In a present of everything, this bitter future of blasted earth, short lives and little choice had surprising appeal. She and her friends loved to play at these games, delineating elaborate rules of privation and oppression. Then, like generations before them had, they set out to make their fantasies real. Be careful what you wish for,-- her mom always said. Little did she know.

43

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, she turned to me and asked, “What’s a woman like you doing in a story like this?” I handed her my card. About a thousand years passed, as her eyebrows worked themselves into a question to which there were at least a dozen answers-- all of them, dead wrong.

67

My mind was going a hundred miles a minute when I heard the voice. “Turn around. Slowly. Drop the book and put your hands up, where I can see them.” In the chilly silence, I could hear a ticking in the shadows behind me. Remembering that face, its numbered hours, I suddenly knew that I’d never be able to kill time again.

71

“If only we had vibrissae,” she murmured, as we crawled through the debris-strewn basement in a dark so complete I was sure I had gone blind. “Then we could sense these obstacles before we run into them, or worse.” Whiskers would help, I thought, as I fell against some hard, sharp-cornered pile of things. Unbidden, though, an image of my grandmother’s bristly moustache approaching my frightened five year old face made me flinch—providentially, slowing my head before slamming into the rocky wall. “Thanks,” I whispered, as I reached up, feeling for the windowsill I hoped I would find.

79

Archaeology horrified her: the idea that, beneath the present layer of clothes, magazines, embarrassing plush animals still lingering from childhood, cheap broken jewelry and discarded electronics, the evidence of another era might be found. Who had lived here before? What other houses were built on this spot? Did a girl live in this room, or a family of four in a tiny shack, or maybe a fox, in a hole in the ground? And how far down would she have to dig to be sure that she wasn’t sleeping each night on top of many others, their collective dreams like an awful piece of cake, bound together by the accident of place?

81

Sometimes in the summer the rain would start in the middle of the night-- a ferocious downpour/ opened spigot blown sideways into every room/ thunder and lightning waking and frightening everyone in miles, flashing and booming with such ear-splitting force that you thought for sure the house was hit. You’d fall out of bed and run to shut the windows, then, trembling, sink back on the rucked-up sheets and drift back to sleep as the storm moved away. In the morning you’d sometimes wonder if it had really happened, so little proof remained once the sun was up.

93

The son of a couple in the godforsaken town where your grandfather lives has a badly twisted spine. One day you are walking alone near the woods and the couple, who are tricksters, drive up in their big black car. You get in. The boy is with them, almost your age, and somehow they persuade you to wear his body—just for an hour, the woman croons. Suddenly you’re sitting by the side of the road, your head feeling strangely off-center as you look up and see yourself between them, driving away. They don’t come back. Later, your dog comes and knows it is you, inside the broken boy. As he cries and licks your hand, you wake up.